Famous Americans

Famous African Americans ... Famous Virginians

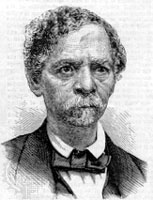

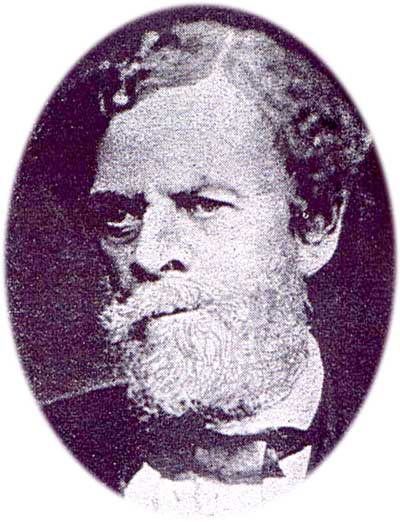

Joseph Jenkins Roberts

1809 - 1876

Summary ... Video ... Color Page ... Pictures ... Netlinks ... Timeline ... Biography ... ProjectsJoseph Jenkins Roberts was born in Norfolk, Virginia.

Unlike most African Americans at the time, Joseph was born free. He was not a slave.

Joseph learned the shipping business from his father.

After his father's death, Joseph's family moved to Liberia in Africa.

Joseph Jenkins Roberts was a successful businessman in the new colony.

Joseph became governor of the colony.

When the colony became a nation, Joseph Jenking Roberts was elected the first president.

Several years later, Roberts was elected to serve another term as president.

Joseph Jenkins Roberts died in office.

Video for J J Roberts

Color J J Roberts

A Coloring Page

Pictures of J J Roberts

Netlinks for Joseph Jenkins Roberts

Timeline for J J Roberts

Projects for J J Roberts

Biography for J J Roberts

VIRGINIA'S NINTH PRESIDENT

JOSEPH JENKINS ROBERTS

Edited by C. W. Tazewell

W. S. DAWSON CO.

Virginia Beach VA 23466

VIRGINIA'S NINTH PRESIDENT: Joseph Jenkins Roberts

An anthology on President Joseph Jenkins Roberts (1809-1876)

with information on Liberia and the American Colonization

Society.

C. W. Tazewell (1917- ), Editor

ISBN 1-57000-052-2 (online), LCCN 90-80507

(Printed version ISBN 1-878515-23-3)

Copyright @ 1992 by C. W. Tazewell

The Editor is grateful for the assistance by Lucile W.

Pearce (1921-1974) in certain of the research for this

publication.

THE EDITOR: Lt. Col. Calvert Walke ("Bill") Tazewell

retired over 32 years ago as a Regular Officer of the United

States Air Force in which he was a

communications-electronics manager and meteorologist. Since

retirement he has been active with historical, library,

environmental, consumer, civil defense, amateur radio, and

youth organizations. He has 15 years experience with

microcomputers. He was the organizer and first head of a

library system for a million people. He was founder and

first president of the Virginia History Federation, and of

the present Norfolk Historical Society (now honorary

president and life member of the latter). He is a writer,

historian and publisher, and has been listed in various U.S.

and British biographical publications. He was raised in

Norfolk and attended Norfolk Academy and Maury High School

W. S. DAWSON CO.

P.O. Box 62823

Virginia Beach VA 23466

a shoestring publisher

C O N T E N T S

Page Numbers Refer to Printed Version

Inscription on Monument in Monrovia . . . . . 4

Picture of Joseph Jenkins Roberts . . . . . 5

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Virginia's Other Presidents . . . . . . . 9

Father of Liberia . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Father of His Country . . . . . . . . . 16

To Observe Joseph Jenkins Roberts Day . . . . 20

First President of Liberia . . . . . . . . 23

The President of the Liberian Nation, Norfolk . 24

Virginia Gets Liberian Flag on Roberts Day . . 24

Four Virginia Negroes . . . . . . . . . 26

Marker to Honor Librarian Leader . . . . . 27

Liberian Envoy to Honor Roberts . . . . . . 27

Roberts Had Faith in Liberia . . . . . . . 29

Roberts Native of Portsmouth . . . . . . . 30

Native of Norfolk Rather Than Petersburg . . . 30

The Americo-Liberians . . . . . . . . . 32

Survival Due To "Vigorous Management" . . . . 38

Devoted His Life To Liberia . . . . . . . 40

Update - A Current View . . . . . . . . 41

All Hail, Liberia, Hail! . . . . . . . . 43

Liberian Adventures Captivate Students . . . . 43

Emerging Liberia . . . . . . . . . . . 45

The Changing Continent . . . . . . . . . 47

Education in Liberia . . . . . . . . . . 48

American Colonization Society . . . . . . . 51

Accounts from Liberia . . . . . . . . . 54

Slaves Rejected Liberty In Liberia . . . . . 55

Membership Certificate in Society . . . . . 57

Called to Serve . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Threat to Future of Nation . . . . . . . . 58

Their Condition a Sad One . . . . . . . . 60

Provisional Constitution and Ordinances . . . 61

More Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

P R E F A C E

Mrs. Pat Matthews wrote in a 1974 letter about J. J.

Roberts, "I feel he is deserving of much fuller treatment

than a magazine article, but I have certain gaps in his life

where there seems to be little information available.

Virginia State College in Petersburg has very little. At

one time there was a large collection of letters, mainly

between Roberts and Colson, but these have been lost. I

tried writing Liberia and the Liberian Embassy with no

results. My best source was the Virginia State Library in

Richmond, and I'm sure there is a great deal of material in

the Library of Congress in Washington."

From time to time for over 25 years I have been trying

to obtain local recognition of the most distinguished person

born in Norfolk, Virginia. I believe that the community

should have an awareness of the contributions and genius of

this famous Virginian. I am sharing this collection of

material on Roberts for use and reference by others with the

hope that it will encourage more interest in and writing on

him.

In January, 1974, I wrote that I had been "interested

in Roberts for almost ten years. While I was active with

the Norfolk Historical Society, I noticed that he was a

local history figure that was not properly recognized by

either the black or white community.... I endeavored to

have Roberts recognized in the local black history program

and in the Norfolk schools, apparently without any

particular success.

"Not too long ago I went to the Norfolk State College

Library to inquire about him and no one I talked to had

heard of him and they were not able to find any material.

Actually I feel that it would be very appropriate for

Norfolk State College to be named for Roberts, especially if

it should become a university (as it probably will in

time)...."

A visit to the Norfolk State University Library the

other day was more rewarding. The reference librarian on

duty said she was a black history buff and well acquainted

with Roberts. She provided me with a useful biographical

citation, and reminded me that the Roberts Village public

housing project was named for J. J. Roberts. She also said

there were Monrovia and Liberia streets in the project.

A writing campaign of over two dozen letters suggesting

that Roberts be noted in Black History Month in 1992 has

produced no results observed by me or the alert staff of the

Local History Section of the Norfolk Public Library. No

answers were received to any of the letters to white and

black leaders, educators and members of the press.

Calvert Walke Tazewell

Virginia Beach, Va.

February 1992

VIRGINIA'S OTHER PRESIDENTS

MONROVIA, Liberia. Ask any Virginia fourth grader how

many Presidents were born in his State, and he will name

eight for you- Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe,

Taylor, Tyler, Harrison and Wilson. He probably will not

know, though, that Virginia also produced Presidents for the

Republic of Liberia in West Africa.

In the shiploads of free Negroes which left Hampton

Roads for Liberia in the early 19th century, were three

Virginians who would lead the new nation in the first

decades of its independence. They were Joseph Jenkins

Roberts (1848-56 and 1872-76), James Spriggs Payne (1868-70

and 1876-78), and Anthony William Gardiner (1878-83).

The foremost of these men, J. J. Roberts, was born in

Norfolk on March 15, 1809. The city had just been through a

boom period in its shipping and growth, and it was busily

paving muddy roads, setting up street lights, and erecting

new brick buildings. Roberts was a freeborn Negro, the

oldest of seven children. One of his early jobs was on a

James River flatboat carrying goods from Petersburg to the

Norfolk docks.

After the death of their father, the Roberts family

moved to Petersburg where they learned of plans to colonize

parts of the African coast. Several shiploads had already

sailed from Norfolk under the sponsorship of the American

Colonization Society. They had settled at the mouth of the

Mesurado River at 6 degrees 20' north latitude, and were

calling their little town Monrovia, after U. S. President

James Monroe.

The Roberts family joined a group sailing on the ship

Harriet on February 9, 1829. Also on board was James S.

Payne of Richmond, who would become the second Virginian

President of Liberia. A few days before the ship docked at

Monrovia, Roberts celebrated his 20th birthday.

In the new colony, the family built a house on their

allotted land, and the brothers began trading in palm

products, camwood, and ivory. The success of the business

enabled them to purchase ships for trade with other coastal

ports. One of the brothers studied in the United States and

became a physician. Another was a minister, the frist

Methodist bishop of Liberia.

At the age of 24, J. J. Roberts was appointed high

sheriff of the colony. His duties involved leading

expeditions to collect taxes or put down uprisings in the

tribal towns near Monrovia. In 1838, the society appointed

him vice governor, and when the governor died two years

later, he became its first non-white leader.

The 1840's were decisive years for the settlement.

Britain and France, which held neighboring territories (now

Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast), viewed Monrovia as merely a

small private venture without the official support of any

recognized government. The American Colonization Society

advised the colony to declare its independence so that it

could claim international recognition and rights.

Late in 1846, Governor Roberts called for a referendum

in Monrovia and three nearby settlements. The settlers

voted for independence, and Roberts was elected the first

President of the republic.

The new nation still had unresolved problems of

territorial limits and jurisdiction. President Roberts

extended the boundaries through treaties and purchases from

tribal chiefs. He took steps to halt slave trading in the

interior and to bring tribal chiefs into the central

legislature.

After four terms, Roberts lost the 1855 election. He

then served 15 years as a major general in the Liberian army

and later as a diplomatic representative to France and

England.

Roberts helped to organize Liberia College, served as

its first president, and traveled often to the United States

to speak and raise funds. He remained the college's

professor of jurisprudence and international law until his

death.

In 1871 the incumbent President of Liberia was

disposed, and the legislature declared J. J. Roberts the

President for another two years. He then won a sixth term,

which he completed a year before his death in 1876. In his

will he left $10,000 and a rubber farm for the support of

education.

The name of J. J. Roberts is well known in Liberia

today. Monrovia, a city of 80,000, has a Roberts Street and

two monuments honoring him. The nation's airport is

internationally known as Robertsfield, and one of the

growing coastal cities is called Robertsport.

March 15, Roberts's birthday, is a holiday when all

schools and businesses halt for the festivities of speeches,

parades, and dancing. Liberians don their best outfits for

the occasion- the women wearing colorful "lappa" dresses and

headties. Throughout the country, descendants of early

settlers join with present-day tribesmen to honor the

Virginian who was the founder of their nation. Judith Evans

Brown in THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT, March 17, 1968

THE FATHER OF LIBERIA

Although every American schoolboy learns that the

Father of his Country as George Washington, few realize that

another son of the Old Dominion also deserves that title.

Joseph Jenkins Roberts was born in Norfolk in 1809,

emigrated to Africa while he was a young man, and led the

small colony of Liberia to it emergence as an independent

republic in 1848. The tiny outpost of the American Society

for the Colonization the Free People of Color had a

population of more than six hundred when Roberts arrived in

1829. During its colonial period he served as sheriff,

chief justice, lieutenant governor, and governor of the

African settlement. When Liberia became independent, he was

elected the first president of the new nation.

Educated and poised, Roberts- an octoroon- came from

the Negro elite of the Old Dominion. His mother, Amelia,

was described by a white contemporary as a woman of

"intelligence, moral character, and industrious habits."

She had gained her freedom from slavery despite the

stringent laws of Virginia's black code and had soon managed

to place herself "on comfortable circumstances." Although

Joseph's paternity is uncertain, he was brought up as the

son of Amelia's husband, James Roberts, a free Negro who had

established his own boating business on the James River.

While Roberts was still a child, the family moved to

Petersburg. The elder Roberts began to transport goods on

his own flatboats from Petersburg to the wharves of Norfolk

and, by the time of his death, had accumulated substantial

wealth for a free Negro of his day. He left his wife and

family two houses and several boats and parcels of land, as

well as other property. In a day when most Negroes were

propertyless slaves, his acquisition of material goods was

impressive.

The Roberts were undoubtedly among the more ambitious

of the free Negro families in Virginia. Of the seven

Roberts children who emigrated with their mother to Liberia

after the death of their father, three of five sons came to

hold important positions in the colony. Two of Joseph's

younger brothers deserve special notice: Henry J. Roberts

left Liberia to study at the Berkshire Medical School in

Massachusetts and then returned to establish a popular

practice in Monrovia, the capital of the colony; John Wright

Roberts became bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in

Liberia and ministered to a body of almost two thousand

members.

It was Joseph Jenkins Roberts who brought the family

its greatest distinction. As a boy in Petersburg, he had

learned not only his father's trade but had also served as

an apprentice in a barber shop. He was thus trained in two

of the most lucrative occupations open to fee Negroes of his

day. His apprenticeship brought him into close association

with one of Virginia's best educated and most outstanding

black residents, William N. Colson, a minister of the gospel

and the owner of the barber shop in which Roberts served.

Colson allowed young Joseph access to his private library,

from which he acquired much of his early education.

The factors that lead Joseph and his mother, brothers

and sisters to emigrate are not known, but undoubtedly the

restrictions of the Virginia black code played a part.

Young and enterprising, Joseph must have been looking for a

better way to make use of his talents. As he began to think

of emigrating to Liberia, he and Colson talked of the

possibility of establishing a transatlantic trading company

that would carry African products to American ports, and

American goods and black emigrants to Liberia.

The religious beliefs of the Roberts family were also

important in their decision to emigrate. The colonization

movement had gained wide support among Virginia churches,

and the Roberts family- faithful members of the

predominantly white Union Street Methodist Church in

Petersburg- were caught up in the missionary zeal that swept

over the United States in the years before the War of 1812.

By going to Africa, they expected to help spread

"Christianity and civilization" among the natives of the

"Dark Continent."

On February 9, 1829, the Roberts family sailed from

Norfolk on the ship HARRIET. After their arrival in

Liberia, they suffered from the dreaded "African fever."

Although living conditions there were very different,

Joseph's mother wrote that they were "pleased with the

country." and had "not the least desire to return to

Virginia."

In 1829, the African colony was just emerging from the

ravages of disease and hostile natives that had almost

destroyed the small settlement. Though troubles continued,

the colony became sufficiently stable to begin significant

economic expansion, and Roberts capitalized on the

situation. With the help of sympathetic white Americans,

Roberts, in Liberia, and Colson, in Petersburg, began to

organize the trading company that they had previously

planned. By the early 1830s they were transporting hides,

ivory, camwood, palm products, and other African goods to

New York, Philadelphia, and other American ports. Roberts

became as adept at trading with the natives as some of the

best African tradesmen, and he established a company store

in Monrovia in which he sold the products furnished by

Colson.

Within a few years, Colson decided that he too would

emigrate to Liberia. The business was prospering, and

Colson, like Roberts, longed to spread Christianity among

the natives. In 1834, he wrote the American Colonization

Society that he did not want to go to Africa purely for

financial profit: he also hoped to "do good." He would not,

he declared, transport liquor to the colonies or sell it to

the inhabitants. By the following January, Colson had

decided to charter a vessel to transport more than fifty

emigrants. He sailed to the African coast later that year,

but soon after his arrival and his reunion with Roberts he

succumbed to the African fever. Roberts, then in his

mid-twenties, wrote Colson's wife, who had remained in

Petersburg to supervise the purchase of supplies for the

company: "Would to God I could say something in this your

time of trouble but this I will say you must remember ...

though [it] seems hard at this time, God does all things

well for them that live and fear him."

After Colson's death, Roberts's trading ventures

continued. Her had already become heavily involved in

colonial politics, and he had gained the confidence of the

white official of the colonization society by protesting

against the slave trade that some unscrupulous Liberians

were carrying on. In 1833 he had been elected high sheriff

of the colony. His duties included responsibility for the

supervisions of elections and for controlling nearby tribes.

Roberts carried out his duties effectively, using diplomacy

whenever possible and resorting to force only when

necessary.

Roberts's success in handling domestic problems led to

his appointment as lieutenant governor in 1839. The

colonization society, in order to provide more autonomy for

Liberia and to ease its own financial burdens, revised the

constitution it had previously provided for Liberia. The

governor of the colony, heretofore the mere agent of the

society, became chief executive of the colony. After the

death of Governor Thomas Buchanan (a Pennsylvanian and the

brother of James Buchanan, who became president of the

United States), Roberts became the first black governor of

Liberia. Under his leadership, as governor from 1842 to

1848 and as president from 1848 to 1855 and from 1871 to

1876, Liberia grew until it stretched along the African

coast from the Sherbro River to the Pedor River, a distance

of nearly six hundred miles.

Roberts's genius as a leader lay in his diplomatic

abilities: he dealt effectively with African tribes and

maneuvered skillfully in the complex field of international

law. His leadership in the colony's efforts to secure its

sovereignty and independence was subtle and calculated.

Even in the 1840s, before the colonization society decided

that it could not carry its burden of responsibility for the

colony's economic well-being, Roberts had begun to argue

that Liberia was an independent nation. Its people, he

maintained, had gained their sovereignty upon emigrating

from the United States. He informed European nations

trading on the African coast that they must deal with

Liberia as an independent state. In 1846 Roberts urged the

Liberian legislature to "announce" the independence of the

country and yet to maintain the continued "co-operation and

assistance" of the colonization society. The legislature

agreed to do so if the people approved. After a close

referendum, Roberts declared that they had voted in favor of

independence. A convention was called to establish a

constitution for the new nation, and Roberts became

president under its provisions.

In 1848, he sailed to Europe to obtain formal

recognition for the new republic. He was well received in

Europe and made to feel welcome in the courts of Queen

Victoria and Napoleon III. Both France and England agreed

to recognize Liberian independence. In 1849, Roberts

returned to Africa with a gift from Queen Victoria: a

four-gun cutter to patrol the coast against slave traders.

At ease with the leaders of the most powerful European

nations, Roberts also found welcome in the United States and

in his native Virginia. On several occasions he returned to

the United States for visits. When Roberts came to America

in 1844, General John Hartwell Cocke, one of Virginia's most

prominent planters and an ardent supporter of the

colonization movement, urged the Liberian to visit him at

Bremo, his home in Fluvanna County. Cocke wrote to the

American Colonization Society: "There is no Governor on

earth, I should entertain with more pleasure than the Chief

Magistrate of Liberia."

After Roberts death in 1876, the Petersburg INDEX AND

APPEAL wrote that his career had been a source of pride to

many blacks throughout the country and especially to his

friends and relatives in Petersburg. Within the last

century, Liberians have honored his memory by erecting two

monuments to him in Monrovia. The nation's leading airport,

Robertsfield, and the growing coastal city of Robertsport

both bear his name, and March 15, the day of his birth, is a

national holiday. Only in more recent years has American

interest revived in the skillful, forceful Virginian who led

a handful of black settlers on the coast of Africa to

independence and nationhood. Pat Matthews in VIRGINIA

CAVALCADE, Autumn 1973, p. 5-11, plus full-page color

portrait of Roberts by Thomas Wilcox Sully. The article

includes many illustrations. Pat Matthews is a former

newspaper reporter who was doing free-lance writing.

George H. Tucker wrote a column that briefly presented

Mrs. Matthews article, stating, "Joseph Jenkins Roberts, an

almost forgotten distinguished early 19th century

Norfolkian, has received belated recognition in an

informative and well-illustrated article by Pat Matthews

..." "Tidewater Landfalls," in THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT, Dec. 10,

1973

FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY

Joseph Jenkins Roberts, often called the Father of his

country, was born of free parents in Norfolk, Virginia, on

March 15, 1809. After the death of his father in 1829, his

mother sailed for Liberia with her three sons. The second

of the brothers, John Wright, entered the ministry of the

Methodist Church, and later became Bishop of Liberia; the

youngest son, Henry, studied medicine and practiced for many

years in Liberia; and Joseph decided to engage in trade.

In 1839 he was appointed Storekeeper under Governor

Buchanan. When Liberia became a commonwealth, he was

elected lieutenant-governor. After the death of Governor

Buchanan in 1841, the Colonization Society appointed Roberts

governor.

During this time he had many experiences with the

natives. In 1838, he went as a colonel on an expedition to

Little Bassa to settle a dispute with them over some land

which belonged to the Colonization Society. With a force of

seventy armed men, Roberts took formal possession of the

region.

The Galas, Ballasada and Bopolo chiefs had entered into

a treaty with the government and agreed to submit all

disputes to arbitration. In 1843, the Ballasada asked

permission to go to war against the Bopolo, who had killed

six Ballasada men. Roberts was able to persuade the chiefs

to talk the matter over and make peace.

In the latter part of 1843, Governor Roberts went with

Commodore Perry to visit the coastal settlements. Upon

reaching Sinoe, they called a council of Kru chiefs to

decide a murder case. As a result of the Council, the

chiefs agreed to give up slave trading, to admit and protect

missionaries, to allow the Liberian Government to settle

disputes between tribes, and not to permit any foreign

nation to gain title to their land.

When the Liberian colonies were first organized, they

received aid and friendship from most European officials.

Only the slave traders were hostile. But as the colonies

became stronger and began to buy land, declare ports of

entry, and levy customs duties and harbor dues, relations

with the British traders became less and less friendly.

In 1845, a British brig entered the harbor of Grand

Bassa and seized a schooner belonging to Stephen Benson.

They sent word that the schooner had been seized on

suspicion of being a slaver, and although the vessel was

acquitted in the Vice-Admiralty Court, Benson was orders to

pay the charges of the trial and the captures cost. This

case was presented to the British Government without result.

Finally, the problems of the colony in regard to

British traders was laid formally before the British

Government. The Secretary of State in Washington was asked

what responsibility the United States accepted for Liberia.

He replied that the United States considered Liberia as an

independent nation and took no responsibility for its

affairs.

On June 27, 1847, Hilary Teage, Beverly R. Wilson, J.

N. Lewis, S. Benedict, J. B. Grisson, John Day, Amos

Harring, A. W. Gardiner, E. Titlor, and R. E. Murray, the

elected delegates, met in convention and declared Liberia's

independence.

In October 1847, Joseph Jenkins Roberts was elected

first President of the Republic of Liberia.

President Roberts soon left for Europe for the purpose

of gaining recognition for the new nation. England was the

first country to give Liberia formal recognition, and France

soon followed. England presented Liberia with a small

transport vessel and a gunboat, and signed a commercial

treaty with the new country. France gave a gunboat. In

1849 Liberia was formally recognized by Portugal, Brazil,

Sardinia, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Hamburg, Bremen,

Lubeck, and Haiti. However, the United States did not

recognize Liberia until 1862.

For eight years, President Roberts guided the affairs

of the nation. A party system was adopted, similar to that

in the United States, and new commerce laws passed.

During this time, a native chief, Grando, had been

giving constant trouble to the colony. Grando was suspected

of the murder of Governor Finley, of Sinoe, and it was said

that he had given more to the colony than any other chief.

In 1850, President Roberts invited the people of Bassa

Cove to decide on the site of the new settlement which was

to be made there. The place chosen was near Fishtown,

Grando's region. Grando first pretended to welcome the new

settlement.

In 1851, when President Roberts was superintending the

laying out of the new settlement. he found a British

steamer, CENTAUR, in the harbor. Commodore Fanshave,

captain of the ship. told President Roberts that Grando had

requested him to help stop the Liberians from settling

there. President Roberts asked Fanshave to invite Grando

aboard the ship. This the commodore did, and Grando came

aboard. He was surprised to see President Roberts there,

and denied the commodore's charges. Later he sought an

interview with the President, convinced him of his

repentance, and begged to be allowed to live in the new

settlement. His request was granted.

For a while, Grando lived peacefully in the settlement.

Then, on November 5, 1851, he attacked the village with

about three hundred warriors, murdering nine settlers,

plundering the homes, and setting fire to the town.

During the next ten days, Grando made two attacks on

the Bassa Cove settlement. Finally President Roberts

arrived on the American ship DALE, while another ship, the

LARK, followed, carrying seventy-five armed men. The

presence of the vessels prevented another attack at this

time.

President Roberts then returned to Monrovia and made

preparations for a stronger campaign against Grando. On

January 1, 1852, he arrived in Buchanan (the new name for

Bassa Cove) with five hundred colonists and about the same

number of native troops.

Grando, meanwhile, had allied himself with Boyer, the

chief at Tradetown. Together they commanded about five

thousand warriors. They made their headquarters in a

strongly fortified town surrounded by swamps.

In an hour and a half of fighting, the colonists drove

Grando's warriors out of the town, and the warriors

retreated to join Boyer at Tradetown. On January 15, the

colonial force was joined by the second regiment. They

attacked Boyer's town, and the colonial army was again

victorious.

There was clear evidence that an English trader named

Lawrence had furnished arms to Grando and Boyer and helped

them in their campaign. Soon after this battle a British

vessel, carrying the British consul, came to the coast.

Without communicating with the Liberian officials, the

consul went to Tradetown, called several chiefs on board the

ship, and had them sign statements denying that they had

sold land to Liberia. Later, an English sloop of war

arrived in Monrovia and sent a dispatch to the government

denying the Liberian right to exercise sovereignty over

Tradetown and stating that England would not allow Lawrence

to be molested.

When President Roberts went to England in 1852, he

reported this matter to the British Government and

Parliament placed an embargo on Tradetown. Boyer was not

able to keep the support of his Bassa allies, and, the

embargo proving effective, he stopped dealing in slaves.

Although many other battles were fought, on the whole

the relations with the natives were friendly and most of the

land was bought with peaceful negotiation.

In 1851, the act to incorporate Liberia College was

passed, and when President Roberts retired from office in

1856, he was at once appointed President of the college.

In 1852, a treaty of amity and commerce was signed with

France, similar to the one signed with England. Liberia was

formally recognized by Belgium the following year.

In 1854, post offices were established in each county,

and an issue of paper money was authorized.

Stephen A. Benson was elected President in 1855, and

Beverly P. Yates was elected Vice-President. The following

year, Roberts as a Major-General, led a force of a hundred

and fifty men to aid the settlement of Harper and

neighboring settlements in their war with the Greboes.

Roberts was again successful in concluding negotiations with

the native chiefs, and a treaty of peace was signed with

them. At the same time Roberts negotiated the terms for the

annexation of the Republic of Maryland to Liberia, and the

two republics were united.

During the administration of President Roye, in 1871,

emissaries were sent to England to negotiate a loan which

was needed for building roads, bridges, and for internal

improvements. When news of the terms of the loan, which

were usurious, reached Monrovia, President Roye was

impeached and the vice-president finished out the term.

At the next election, Roberts was recalled to guide the

nation through the critical situation created by the British

loan. He journeyed to England in an effort to clear up the

terms of the loan as well as to settle a boundary dispute.

He and the British were unable to reach an agreement on the

boundary question, and Roberts was able to secure only

thirty thousand dollars on the loan. For this sum, Liberia

would have to pay back six hundred and sixty-three thousand

dollars.

The strain and discouragement of this trip seriously

impaired Roberts's health, and he became increasingly

feeble. In January 1876, he turned his office over to

President Payne, and he died on February 24. THIS IS

LIBERIA, Stanley A. Davis. NY: The William-Frederick Press,

1953, p. 82-87

TO OBSERVE JOSEPH JENKINS ROBERTS DAY

Among the little nations of the world is the Negro

republic of Liberia on the west coast of Africa. Founded as

an independent state on July 26, 1847, the republic will

celebrate its one hundredth anniversary as a sovereign

nation on July 26, 1947, and continue with an international

exposition during 1948-49. The first president of this

nation and the first president of Liberia College was Joseph

Jenkins Roberts. He was born in Virginia in 1809. This man

achieved distinction as a merchant trader, statesman and

educator. It is therefore fitting that the Negro teachers

of Virginia should honor one of their native sons by

publishing an account of his life in their magazine. It is

likewise appropriate that all the teachers of Virginia

should further honor him by joining in the observance of

Joseph Jenkins Roberts day- March 14, 1947,- the day bearing

the official sanction of Governor Tuck.

Like other noted persons of American history, the

paternity of Roberts is not fully known. He may have been

the offspring of a white man, or of James Roberts, the

lawful Negro husband of his mother, Amelia Roberts. James

Roberts was born free; Amelia Roberts did not become free

until 1804 when she was twenty-three years old. There is

some doubt also concerning his exact birthplace. It was

either Norfolk or Petersburg, and in that section of

Petersburg known as Pocahontas. Certainly Petersburg has

the greater claim on him today inasmuch as his parents lived

here and the existing public and private documents covering

his early life reveal him as a permanent resident of this

town.

The lines for future achievement of Roberts were

clearly marked for him during his years in Petersburg. Here

he followed remunerative occupations, held membership in a

church, pursued an education, belonged to an industrious

family, and moved in the best social circles.

His father or stepfather, James Roberts, was a boatman

and the owner of a variety of craft sailing on the James and

Appomattox rivers. To this business of navigation Joseph

Jenkins was trained. The youth also entered barbering and

worked in a shop operated by William N. Colson. The barber

business brought good income to most free Negroes, and it

did to Roberts. For his spiritual uplift he belonged to the

Methodist Church, the religious body which at that time

showed more concern for the welfare of Negroes than any

other in Virginia. Methodist slaveholders took the lead in

liberating their slaves. For his educational development

two or more schools awaited him. In all probability he

attended the school of John T. Raymond which was operated by

a society of free Negroes on Sundays, or he was taught

privately by a Negro tutor. But like certain presidents of

the United States, this future president of Liberia no doubt

received the greater part of his training by the traditional

American process of self-education and by contact with

aristocratic white persons of the community with whom he

came in close contact.

The industry of his family is proved by their

accumulation of property. More than once James Roberts

bought real estate, and he provided well for his wife and

children. At the time of his death (1823) his real estate

embraced two houses and lots valued at sixteen hundred

dollars and personal property, consisting chiefly of four

boats, valued at six hundred dollars. Several years later

Amelia Roberts sold this property, which, added to the sums

of money earned by her son, Joseph, left them in a position

to engage in higher business pursuits when the opportune

time arrived.

Finally, Joseph J. Roberts enjoyed the association of

the leading free Negroes of the town. Among these were

Anthony D. Williams, Joseph Shepherd, John T. Raymond,

Colson Waring, Nelson Elebeck, and William N. Colson.

Williams was a shoemaker; Shepherd and Raymond were teachers

and property holders; Waring was a preacher and property

holder; Elebeck and Colson were barbers, and property

holders in the second generation. To property ownership,

Colson added learning. By reason of his constant letter

writing, his reading of books on intricate subjects, and his

possession of a private library, the progenitor of the

Colson family of today, in depth of knowledge, easily

surpassed many college bred youth of our day. Colson, a man

of brown complexion, and Roberts, a man of light complexion,

were boon companions and both were highly progressive.

But in spite of the success of these individuals in

Petersburg, there were certain influences operating in

America at this time which led them and free Negroes

everywhere to consider emigration to a foreign land. Two

centuries earlier, groups of Englishmen had migrated from

England to America because of religious oppression; now in

the 1820 decade and later, groups of free negroes were to

migrate from America to Africa because of racial oppression.

In every state of the United States they were granted

important civil rights, but in no state were they granted

complete political rights. Worse still, according to the

pronouncements of the leading statesmen, Negroes were never

to occupy a position of equality with the white race by

making them real citizens.

Sensing the injustice of this situation, but holding

rigidly to the view that America was to forever remain the

white man's country, a number of the most prominent people

in the United States assembled at Washington, D. C. in 1816

and formed the American Colonization Society. Their chief

purpose was to persuade free Negroes and ex-slaves to

emigrate to a foreign land and finance them on the voyage to

this land. The country which the Society secured was

Liberia and to this country, they, with the backing of the

United States government, sent 6,792 emigrants over a period

of thirty-one years (1820-1851). Of this number 2,409 were

Virginia Negroes. One of the companies of emigrants from

Virginia came on the ship HARRIET in 1829. Among her 160

passengers on board was Joseph J. Roberts.

All of the experience gained by this man in Virginia

found ample opportunity for expression in Liberia. He soon

became one of the leading citizens of the country. His

first venture in the new country was to put into operation a

mercantile company which he, Colson, and others had already

organized in Petersburg. It bore the name of "Roberts,

Colson, and Company." Finding such raw products as

dye-woods, hides, ivory, palm oil, and rice in abundance in

Liberia, the company exported these products to merchants in

New York and Philadelphia. They bought a ship, the schooner

CAROLINE for this purpose, and on her return voyage to

Africa, brought over goods of American manufacture, which

Colson's wife had purchased in this country for sale in the

company's store in Monrovia. This export and import

business continued for a number of years, but unfortunately

Colson's connection with the enterprise was lost following

his untimely death in Liberia in 1835.

The business success of these merchant traders and

other met with the approval of the American Colonization

Society. Indeed this organization welcomed any sign of

growth, because it was never their intention to keep

settlers in Liberia in a state of dependence. Rather they

allowed Liberia to follow "the usual evolutionary steps

noted in the growth of many a pioneer nation." First came

the period of colonization, and finally the establishment of

the independent nation. Self government was thus introduced

gradually.

Every step upward was accompanied by the drafting of

the services of Roberts. During the last years of the

colonial period he held minor offices, then during a portion

of the commonwealth he served as governor, and finally when

independence was declared in 1847 he was elected the first

president., with his term beginning in 1848. He served in

this high office for four terms, he retired from

governmental life for a period of twenty-four years, only to

be returned to the presidency in 1872, to serve until his

death in 1876.

But the long years of vacancy as president of the

nation meant for Roberts only as a long a period for

activity as president of Liberia College. Founded (on

paper) by the legislature in 1851, the institution was

assigned to Roberts immediately upon his retirement from the

presidential office in 1856. His was the task of first

securing buildings and equipment for the college. Then

after it was formally opened in 1862, he served as its head

and as professor until his death. Thus during the last four

years of his life's career he was a dual president- of the

college and of the nation. Working against heavy odds, his

institution, the capstone of education in Liberia, was

attended during his administration by three hundred students

in the preparatory department, sixty in college, with only

nine of these finishing with the bachelor's degree. As in

the Southland of the United States at the same time, college

education in Liberia was then in its infant stage.

Into a discussion of the numerous problems of

statecraft which faced Roberts as first president of Liberia

the writer in this short article can not enter. It is

sufficient to note that his tasks were so well performed

that the citizens of this country today hold him in the same

high esteem as Americans hold George Washington, that is,

they style him the father of his country.

The purpose of this sketch is to show the man in his

Virginia setting. In a sense it is an effort to bring him

back home to the days of his youth. For here in Petersburg,

Virginia he was in all probability born, here he was married

in a house which still stands, and here he has lateral

descendants today and direct descendants of his close

friend, William N. Colson.

It is fitting and proper, then, that Virginians of both

races should join hands with Liberia in the celebration of

the one hundredth anniversary of the nation's independent

existence. This we propose to do on March 14, 1947 by the

observance of Joseph Jenkins Roberts day throughout the

schools of the state and by an appropriate ceremony on this

day at the Virginia State College. Luther P. Jackson in

VIRGINIA EDUCATION BULLETIN, January 1947. Dr. Jackson was

stated as a noted historian and civic rights leader, and a

professor at Virginia State College, Petersburg.

FIRST PRESIDENT OF LIBERIA

Joseph Jenkins Roberts (1809-1876), the first President

of Liberia, was born of free Negro parents in Petersburg,

Va. He migrated to Liberia in 1829 with his widowed mother

and younger brothers, and became a merchant. In 1842, he

became the first Negro President of the colony of Liberia.

The colony continued to have difficulty with former

inhabitants of the area, and in an attempt to raise money,

they decided to lay import duties on good brought into

Liberia. This caused international problems, because

Liberia was not a sovereign country or a United States

colony. Roberts visited the U.S. in 1844 in the hope of

adjusting this matter, but the American government avoided

taking a stand in defense of Liberia, because the annexation

of Texas was forcing the slavery question to the front. The

American Colonization Society gave up all claims to Liberian

colony. Roberts returned to Liberia and continued

purchasing land. In 1847, he called a conference at which

the new Republic of Liberia was proclaimed, and he was

elected its first President. He was re-elected in 1849,

1851, and 1853. Roberts signed a commercial treaty with

Britain in 1849. His visits to France and Belgium were

instrumental in achieving recognition for Liberia as a

sovereign country. In 1856, he was elected first president

of the new College of Liberia. In another visit to the U.

S. in 1869, Roberts addressed the annual meeting of the

African Colonization Society at Washington. In 1871, he was

again re-elected President of Liberia and served until his

death in 1876. CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE NEGRO IN

AMERICA by Peter M. Bergman. NY: Harper and Rowe, 1969, p.

92

THE PRESIDENT OF THE LIBERIAN NATION, OF NORFOLK

The Wilmington, (Del.) Commercial of the first inst.,

says: "Joseph J. Roberts became today President of the

Republic of Liberia, in West Africa. He is a native of

Norfolk and went to Liberia more than forty years ago. He

was for six years governor of this colony, and in 1836

became the first president of the new republic. He was

reelected three times, serving eight years. Such is his

popularity, that he has been reelected for a fifth term of

two years. He is a worthy member of the Methodist church.

The Republic of Liberia is attracting numerous colored

emigrants from the United States, and from the West Indies."

Norfolk JOURNAL, Jan. 4, 1872

VIRGINIA GETS LIBERIAN FLAG ON ROBERTS DAY

Tuck, Speaking at Rites,

Hits Trouble-Makers In Race Relations

Petersburg, March 15 (AP)- The United States will take

part in a celebration of the first centennial of Liberia's

independence, Sidney de la Rue of the State Department said

last night.

In an address for "Joseph Jenkins Day" [sic] at

Virginia State College here, said Congress would be asked

for funds for expenses. Liberia became a republic July 26,

1847.

Reporting on recent measures of American aid to the

West African Negro republic, La Rue, special assistant to

the director of the State Department's Office of Eastern and

African Affairs, said:

1. A new harbor at Monrovia, the Liberian capital,

built by an American concern, expected to be ready by

August.

2. The State Department favors an arrangement to

maintain Roberts Field, an airport built in wartime, to

permit continuation of an air link between the United States

and Liberia.

La Rue said the State Department has been "at all times

willing to give sympathetic consideration to any request for

assistance by Liberia."

The Negro republic presented its flag to the

Commonwealth of Virginia tonight at the concluding episode

in a day set aside for the State to pay tribute to Roberts,

one-time Petersburg barber who became Liberia's first

president a century ago.

Dr. F. A. Price, Liberian consul general to the United

States, handed his country's colors to Virginia Conservation

Commissioner William A. Wright, who accepted them on behalf

of Governor Tuck in ceremonies at Virginia State College.

The same program featured the unveiling of a portrait

of Roberts by nine-year-old William Nelson Colson who

emigrated from Petersburg to Liberia with Roberts and became

his associate in a mercantile firm there before the African

settlement grew to Statehood.

In ceremonies her earlier today, Governor Tuck said in

a network radio address that Roberts' rise from his

relatively humble birth to a position of statesmanship was

due to his determination, industry and good common sense.

"Joseph Jenkins Roberts was to Liberia what George

Washington was to the United States," the governor said.

"He was its father."

Tuck, who designated today- eve of the 138th

anniversary of Roberts' birth- as Joseph Jenkins Roberts

Day, took occasion in his radio talk to express belief that

the Negro in America "is closer to attaining the standing as

a citizen he desires than is admitted by the professional

trouble-makers among us representing both races."

The governor said that no real problem existed between

the white and Negro races in Virginia and that there was a

mutual respect and confidence among the vast majority of

both races.

"We understand each other," he said, "and either race

will not tolerate the meddling of outsiders wholly ignorant

of our way of life who are bent upon formenting unrest to

mar these cordial and friendly relationships." THE

VIRGINIAN-PILOT, March 16, 1947

FOUR VIRGINIA NEGROES

Distinguished honors for four Virginia colored men- two

living and two dead- came within a single month.

On March 14, tribute was paid to the memory of Joseph

Jenkins Roberts, born in Petersburg in 1809, first president

of the Republic of Liberia, a country that will celebrate

its centennial on July 26. Born of free parents, Roberts

emigrated to Liberia, where in 1847 he became that country's

first president.

The Virginia General Assembly has appropriated $15,000

to aid in establishment of the Booker T. Washington

Birthplace Memorial. The United States Treasury has

recently issued memorial fifty-cent coins to be sold at a

premium to aid in erection of the memorial. Washington was

born on the Burroughs plantation near Hales Ford in Franklin

County, and educated at Hampton Institute. Following his

founding and development of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama,

there was inscribed on his tombstone: "He lifted the veil of

ignorance from his people and pointed the way to progress

through education and industry."

Plummer Bernard Young, Sr., founded the Norfolk Journal

and Guide in 1910 and is still active in its management,

with his son, P. B., Young, Jr., as editor. It has been

given the Wendell L. Wilkie Journalism Award for having

rendered during 1946 the highest public service of any Negro

newspaper in the United States. The previous year the

Journal and Guide shared two honors with the Pittsburg

Courier. P. B. Young, Sr., was born in Littleton, N. C., in

1848, and after studying at St. Augustine College, raleigh,

settled in Norfolk, where he organized the Tidewater Bank

and Trust Company. In 1943 he was made chairman of the

board of Howard University, Washington, and has in the past

been a trustee of Hampton Institute, of St. Paul's

Polytechnic College, and chairman of the Southern Conference

on Race Relations.

Recently elected to the presidency of Fisk University

is Charles Spurgeon Johnson, a native of Bristol, Va., and a

graduate of Virginia Union University, Richmond, the first

Negro to hold the Fisk presidency. He had been a member of

the faculty since 1928, as director of the department of

social sciences. Recently he served as a member of the

Allied Education Commission which went to Japan at the

request of General MacArthur to make recommendations as to

the Japanese school system.

Recognition of four Virginia Negroes, two living and

two dead, should be an inspiration to all members of that

race, and of satisfaction to all who look for better race

relations and for progress through education and effort.

From the Roanoke World News, in THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT, May 12,

1947.

MARKER TO HONOR LIBERIAN LEADER

PETERSBURG- A memorial marker will be dedicated June 4 in

honor of the years Joseph Jenkins Roberts, often called the

George Washington of Liberia, spent in Petersburg in the

early 1800s....

While president he made a number of visits to the

United States and to Petersburg. In 1869, during an address

at the former Union Street Methodist Church, he told the

crowd that 43 years earlier, at the same place where he

stood, he had made a public profession of religion....

RICHMOND TIMES-DISPATCH April 23, 1978 (date not certain)

[more complete information in item that follows]

LIBERIAN ENVOY TO HONOR ROBERTS

PETERSBURG- Liberian Ambassador Sir Francis Alfonso

Dennis will be the keynote speaker at memorial services

today for Joseph Jenkins Roberts, Liberia's first president

and former Petersburg resident.

The 2:30 p.m. program will be held at Oak Street A.M.E.

Zion Church. The unveiling of a memorial marked next to the

church at Sycamore and Wythe streets is set for 3:30 p.m.,

and a reception is slated for 4 p.m. at the Grand Hotel of

Beaux-Twenty Club.

Community leaders, Liberian representatives and

secondary and college students will be among those at the

services saluting "the George Washington" of Liberia.

Dr. John Rupert Picott, executive director of the

Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History

in washington, will deliver special remarks.

The Liberian national anthem and the "Star-Spangled

Banner" will be among the music played.

The observance stems from the work of Joseph H.

Jenkins, a retired English professor at the Virginia State

College and chairman of the Roberts Memorial Fund.

Jenkins, who is not a descendant of the man being

honored and often is asked if he is, appeared before City

Council in November 1976, urging that a marker be built. In

June 1977, the city provided the site and $1,900 for a

marker and the service.

Through the non-profit foundation, more than $3,000 in

additional contributions was received. A brochure will be

published later this year and will include a biography of

Roberts, his inaugural address and other pertinent writings.

The cover will be a reproduction of a 1844 painting of

Roberts done by Thomas Sully and owned by the Pennsylvania

Historical Society.

Contributions toward the projects here come from many

types of people, and Wert Smith of Smith Advertising, in an

effort to stimulate community awareness of the Roberts

memorial program, donated five billboards to publicize the

project.

"We have taken it slowly and quietly, tried to involve

as many people as possible and the achievement has been

gratifying," Jenkins said.

A 6-foot-long marker, 42 inches high, will be the

monument, Jenkins said, instead of a statue of Roberts.

"The marker provides the dignified recognition in this

community where he once lived. His real achievements were

elsewhere," Jenkins said. "He achieved mightily in Africa

and there are many monuments there,

"The airport in Liberia is named for him, [as is] the

university which he served as president. Here in

Petersburg, where he lived during his formative years, this

marker is sufficient- it indicates he was once a resident

here and that the people here appreciated him."

The inscription on the marker reads, "Joseph Jenkins

Roberts, resident of Petersburg 1809-1829, President of

Liberia 1847-1851, 1868-1876."

On the back it reads, "Joseph Jenkins Roberts worked

100 yards northwest of this spot." The names of the council

members authorizing the memorial also appear.

Roberts, who worked in a barber shop on Union Street

and made his public profession of religion in a church that

used to stand in the neighborhood, would have walked in the

area where the marker stands.

"It is a proper place for the marker," Jenkins said, "a

site associated with black activity in Petersburg and a

place, so visible, city residents and visitors to this city

can't miss it." LeeNora Everett in RICHMOND TIMES-DISPATCH,

June 4, 1978, P. D-1,3 (related story on page D-8) Also,

THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT, June 5, 1978, "Statue of Liberian

Dedicated," stated, "The Liberian ambassador to the United

States referred Sunday to his nation's first president as a

noted general and statesman `who inspired the gratefullness

of succeeding generations of Liberians.'"

ROBERTS HAD FAITH IN LIBERIA

PETERSBURG- On the Jan. 1, 1825 Register of Free Negroes

and Mulattoes in the Petersburg clerk's office appears the

name Joseph Jenkins, son of Amelia Roberts.

Joseph Jenkins Roberts, whose formative years were

spent in Petersburg and who would become the first president

of Liberia, was described in that 1825 registration as "a

lad of colour, 16 years old in March next- rather above 5

feet 6 inches high in shoes, light complexion, grisley or

reddish brown hair..."

It concluded: "he deserves to be registered."

To become registered, blacks had to show they were

needed in the community's labor market. After a court

granted them that status, they carried their legal papers

with them, since they had to be presented upon demand.

At the time Roberts worked in a barber shop on Union

Street and on one of his father's boats, which carried

freight from Petersburg to Norfolk.

Four years later, Roberts went to Liberia under the

sponsorship of the American Colonization Society.

William N. Colson, who had owned the shop where Roberts

had worked, joined in a mercantile operation that included

Roberts....

In 1836, Roberts wrote Sarah H. Colson, wife of his

business partner, to tell her of her husband's untimely

death in Monrovia.

The letter, which is in the archives at Virginia State

Library's Johnston Library, relates that Colson was well

during the passage, but 15 days after his arrival he became

ill with a fever.

Roberts' faith is shown in passages of the letter: "...

the Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away. He works in a

misterious way his wonders to perform, though it seems hard

at this time, God does all things well for them that love

and fear him. You cannot tell for what cause he had

thought proper to remove him from this world of bustle and

confusion, for his part, he is gone to the realms above, he

is gone to Abraham's bosom and expects to meet you there."

From colonization to the era of the commonwealth to the

establishment of an independent nation, Roberts gave his

service to Liberia.

During the last years of the colonial period, he held

minor offices, and when independence was declared in 1847,

he was elected Liberia's first president, his term staring

in the next year....

Today's ceremony honoring Roberts is not the first in

the state.

During the tenure of Gov. William M. Tuck and the 100th

anniversary of Liberia as a nation, Joseph Jenkins Roberts

Day, March 14, 1847, was held in Virginia.

Historian and civil rights leader Luther P. Jackson,

who taught at VSC from 1922 until his death in 1950, saluted

Roberts in the January 1947 Virginia Education Bulletin.

It is fitting, Jackson wrote, "that the Negro teachers

of Virginia should honor one of their native sons by

publishing an account of his life in their magazine,"

emphasizing Roberts' "distinction as a merchant trader,

statesman and an educator."

VSC archivist Lucious Edwards Jr. reflected that

Roberts, who had no formal education, faced a situation in

Liberia similar to the one that exists in the Middle East.

"There were several different kingdoms in Liberia- the

Maryland Colony, the Virginia Colony- he united them, got

their support."

A little-known fact, Edwards said, is that the first

four presidents of Liberia were from Virginia. RICHMOND

TIMES-DISPATCH, June 4, 1978, P. D-8

ROBERTS NATIVE OF PORTSMOUTH

Liberia was founded by free colored people, sent out in

1822 by the American Colonization Society, of which Henry

Clay was president. Joseph Jennings [sic] Roberts, the

first president of the republic, was elected October 5,

1847- he was a native of Portsmouth, and was carried out on

a ship commanded by Capt. Henry Peters. HISTORY OF NORFOLK

COUNTY VIRGINIA AND REPRESENTATIVE CITIZENS, William H.

Stewart. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Co., 1902, p. 384

NATIVE OF NORFOLK RATHER THAN PETERSBURG

A cheerful trend of the period, which, unhappily, did

not accomplish the desired result, was the activity in

Petersburg and nearby counties of auxiliary societies of the

American Colonization Society. The purpose was to encourage

the liberation of Negro slaves and their colonization in

Liberia. Letters of the time often contain references to

vessels sailing from City Point with large numbers of freed

Negroes. The CYRUS made several voyages for the purpose.

When its captain died during one of the journeys, his wife,

Mrs. Pamela Gary, piloted the ship home. A passenger on the

HARRIET in 1829 was Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who was to

become the last governor of Liberia under the American

Colonization Society and the first president of the

independent nation. Roberts probably was a native of

Norfolk rather than Petersburg, but he long made his home in

Petersburg. Liberia enjoyed its most successful years under

his leadership, and local esteem for him was shown during

his several visits to Petersburg. PETERSBURG'S STORY: A

HISTORY. James G. Scott and Edward A. Wyatt, IV.

Petersburg, Va.: Titmus Optical Co., 1960, p. 64-65

THE AMERICO-LIBERIANS

... But it resulted in a new and very practicable

document's being adopted by the Society, known as the

Constitution of 1838. This was brought to the colony by

Governor Buchanan, who arrived at Monrovia on April 1, 1839.

On landing, he presented the new constitution to the

settlers. It was accepted by unanimous vote, subject to one

slight change that was later agreed to by the Society. The

colonists thus, for the first time, themselves in effect

enacted a constitution. They might have objected to the

Society's document, might have insisted on their own. That

they did not do so was the act of a free people, an act of

sovereignty. The Constitution of 1838 became their own

constitution. The Society remained the servant, not the

master of the settlers.

Governor Buchanan's administration was constructive.

In particular he addressed himself to breaking up the slave

trade still carried on at points along the coast, notably by

groups of Spaniards who had slave "factories" at a distance

from Monrovia in the direction of Cape Mount. Buchanan let

his zeal outrun his authority (he was also United States

agent) but he was never seriously called to account, and his

actions went far toward the final destruction of the slave

trade.

There were others than slavers who had a foothold on

the Liberian coast. British traders had for many years

maintained establishments for dealing with the natives,

bartering so-called "trade goods" for ivory, palm oil, and

other local products. These traders denied the right of the

new Liberian Government to control trading within the

territory over which the colonists claimed sovereignty. In

particular, they denied the right of the colony to exact

customs duties. They were upheld in their denial by

officers of the British Navy, operating off the coast.

Soon after Buchanan's accession as governor, the matter

of the British right to trade regardless of Liberian laws

came to a head. A British subject was accused of trading in

defiance of the colonial laws and was brought before the

Liberian court. The legal question involved in the case

(Commonwealth of Liberia vs. John G. Jackson, Master of the

British schooner Guineaman) was a close one, turning on

whether or not his act in taking aboard a cask of palm oil

constituted trading. The case was tried before Lieutenant

Governor J. J. Roberts, sitting as Chief Justice. Mr.

Roberts was later to become Liberia's first President. The

facts in the case were well established. Roberts' charge to

the jury is remarkable for its fairness and for its clear

expression of the difficult legal points involved. It led

to a verdict of guilty and the defendant was fined,

protesting that he would bring the matter before Her

Majesty's Government and if necessary before Parliament.

The real issue was Liberia's right as a sovereign nation to

govern its territory and territorial waters, a right

constantly denied by the British.

Two points about this case are especially noteworthy:

first, the carrying of the matter into court by the

Liberians; and second, the personality of the presiding

judge. Joseph Jenkins Roberts was a Negro, born free in the

United States, where he had received a liberal education,

which did not, however, include the law. He had, in fact,

followed mercantile pursuits, establishing in Liberia a

successful trading company and owning vessels. Yet his

charge to the jury was a masterpiece, its legal soundness

never successfully challenged.

Governor Buchanan died at Bassa Cove September 3, 1841.

Lieutenant Governor Roberts succeeded him and was affirmed

as Governor by the Society the following January.

The constant denial of the European powers, especially

Great Britain, of the right of Liberia to exercise

sovereignty continued to be the chief concern of the

administration at Monrovia. The colony will still pitifully

small and weak, numerically and physically. Exclusive of

recaptured Africans and natives, it numbered less than three

thousand. But it was strong in purpose and its leadership

was acquiring formidable stature. That this little group of

people should come to such a degree of political maturity

within two decades is astonishing. Their task had been more

than one of creating a settlement against heavy odds; they

now had to face the might of the British Government. David

was to meet Goliath.

The British, in the person of their naval officers,

persisted in resisting Liberian sovereignty. The position

of Her Majesty's Government was stated by Captain Denman,

R.N., who claimed that "as British traders had for a long

series of years carried on an undisturbed trade with the

natives," at Bassa Cove in particular, the Liberians had "no

right now to insist upon their compliance with any

regulation made by the Government of Liberia."

By 1843 the matter was in diplomatic channels, with the

British trying to pin down American policy. The British

minister in Washington was instructed to address Secretary

of State Upshur, inquiring as to the degree of official

patronage and protection accorded Liberia by the United

States and, if such protection was extended, requesting a

definition of the geographical limits of Liberia. To this

inquiry Secretary Upshur replied, setting forth clearly that

Liberia had no political relationship with the United

States. He skirted around the question of Liberia's

sovereignty, but said that the United States "would be very

unwilling to see it [Liberia] despoiled of its territory

rightfully acquired, or improperly restrained in the

exercise of its necessary rights and powers as an

independent settlement."

With this mild warning to the British from Washington,

Liberia was left to fend for itself. And the British

resistance continued.

Governor Roberts, in a message to the legislative

council dated January 18, 1845, recited the reiterated

position of the British as communicated to him by Commodore

Jones of H.M. Ship Penelope. "The Liberian settlers," said

Commodore Jones, "have asserted rights over the British

subjects alluded to [traders on the coast] which appear to

be ... inadmissible on the grounds on which Liberia's

settlers endeavor to found them For the rights in question,

those imposing customs duties and limiting the trade of

foreigners by restrictions, are sovereign rights, which can

only be lawfully exercises by sovereign and independent

states, within their own borders and dominions. I need not

remind your Excellency that this description does not apply

to `Liberia' which is not recognized as a subsisting state."

In reporting to his council this statement of Commodore

Jones, Governor Roberts presented an able argument in

refutation and then said, "I feel, gentlemen, that the

position assumed by the British officers ... will not be

sanctioned by the British Government. In the meantime, I

would advise [that] a statement, setting forth the facts in

relation to the misunderstandings that have arisen between

the Colonial Authorities and British subjects, trading at

Bassa Cove, be furnished the British Government by the

people of Liberia."

But this dignified and exceedingly diplomatic position

taken by Mr. Roberts, in reliance upon the British sense of

fair play, was of no avail. In April, 1845, Her Majesty's

brig Lily entered the harbor of Grand Bassa, seized a

Liberian schooner, the John Seys, on suspicion of being

engaged in the slave trade, and took it to Sierra Leone for

adjudication. Here the schooner was fully acquitted of the

slaving charge by the admiralty court. But the entire cost

of the proceeding was assessed against the vessel and the

British continued to hold the John Seys on the pretext that

the Liberian settlers possessed no sovereign rights, that

they were not authorized to establish a national flag, and

that the John Seys was therefore a vessel having no flag, no

national character.

This was the last straw. Governor Roberts was now

arguing on familiar ground. "I am decidedly of opinion,"

said he, "that the Commonwealth of Liberia, notwithstanding

its connection with the Colonization Society, is a sovereign

independent state, fully competent to exercise all the

powers of government ... [and that] the citizens of Liberia,

as an infant Republic, entered into a league or compact with

the Society, confiding to them the management of certain

external concerns.... In this no surrender of sovereignty as

a body politic was ever contemplated by the Liberians or

understood by the Society.... That an arrangement so novel

and without precedent should in its operations experience

some jarrings is not surprising.... We have associated the

idea that colonies have always commenced their existence in

a state of political subjection to and dependence on a

mother country, and for that reason could not be sovereign

states nor exercise the powers of sovereignty until the

dependence was terminated. Hence we often talk as if

Liberia needed to go through the same operation. But

Liberia never was such a colony; she never was in that state

of dependence, and therefore needs no such process in order

to become a sovereign state."

It is significant, and certainly speaks volumes for the

soundness of Mr. Roberts' argument, that a full century

later, Dr. Huberich, a world-renowned authority on

international law, reached the same conclusion as did the

Liberian Governor, and by the same general line of

reasoning.

"That settlement," says Dr. Huberich, speaking of the

landing at Cape Mesurado, "marks the beginning of a new

state, not the settlement of a colony. The settlers did not

retain any political connection or remain in subordination

to any foreign power. They created a state of their own....

As an independent sovereign state the settlement had power

to extend its frontiers, and acquire sovereignty over the

territories acquired by it, and to subject all persons,

whether its own citizens or foreigners, to its laws and the

jurisdiction of its courts, in the same manner and subject

to the same limitations as are imposed by international law

on all states. The British and French Governments were,

therefore, wrong in their contentions that the Settlement

could not acquire additional territory, and subject the

foreign traders to the laws of the Settlement extended over

the new acquisitions. It had the right to subject foreign

vessels within its territorial waters to its regulations and

port charges, and impose customs duties on foreign imports."

Certain as he was that Liberia possessed and always had

possessed the rights of a sovereign power, Governor Roberts

nevertheless recognized the confusion that existed in

people's minds because of the peculiar relationship with the

Colonization Society. He felt that the time had come to

sever that relationship; that his country was not ready for

self-government.

"That some measures should be adopted," said the

Governor to his legislative council, "which may possibly

relieve us from the present embarrassments is very clear,

but how far it is necessary to change our relationship with

the Colonization Society for that purpose is a matter for

deep consideration.... In my opinion, it only remains for

the Government of Liberia, by formal act, to announce her

independence- that she is now and always has been a

sovereign independent state; and that documents of this

proceeding, duly certified by the Colonization Society, be

presented to the British and well as to other governments,

and by that means obtain from Great Britain and the other

powers just and formal recognition of the Government of

Liberia."

Governor Roberts was not unmindful of the fact that,

sovereign or no sovereign, Liberia owed its existence to the

Society. Continuing, he said: "We should remembers with

feelings of deep gratitude the obligations we are under to

the American Colonization Society; they have made us what we

are, and they are deeply interested in our welfare; and I

firmly believe they will place no obstructions in the way of

our future advancement and final success."

So the question of sovereignty and independence were

referred to the Society. On receipt of the Society's reply

an extra session of the council was called, meeting July

13-15, 1846. After a calm dispassionate discussion of the